Eugène Vidocq

Eugène François Vidocq . (by Achille Deveria)

“The one thing certain about Eugène François Vidocq was that nothing was certain. He aged as he had lived, a chameleon.” - E. J. Wagner

What we know about Eugène François (or François Eugène) Vidocq is an intriguing mixture of fact and fiction. He was born in 1775 (or 1773) in Arras, the son of a baker (most likely). During the opening of a London exhibit of his memorabilia in 1845, the Times of London described him as standing 5’10” but able to appear shorter, while other sources in attendance described him as short, no more than 5’6” but able to make himself seem taller.

Perhaps the best way to describe Vidocq is that his life reads like an Honoré de Balzac novel, or Victor Hugo, or Robert Louis Stevenson. He was a close associate of France’s great authors, acting as inspiration for Eugène Sue, Alexandre Dumas (senior), and Emile Gaboriau. Balzac’s character Vautrin, is an obvious nod to Vidocq (a reformed criminal who becomes the Chief of Police) who is, in turn, the inspiration for Hugo’s Javert in Les Miserables.

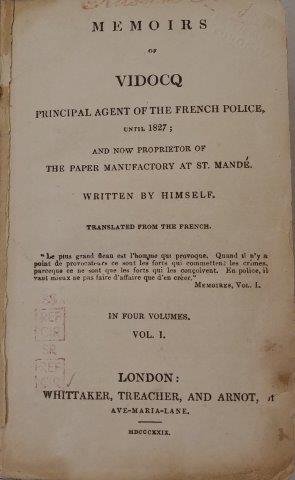

These same literary giants encouraged Vidocq to write a memoir, and, perhaps, inspired him to embellish the truth. The authenticity of his Mémoirs (first published in 1828) is debatable, and from its first appearance, accusations of embellishment were made. Several volumes exist, each with subtle, but telling, differences, the fourth of which Vidocq vehemently denounced as false. He attempted to correct the errors by persuading others to publish his accounts of events under the title of Les Vrais Mémoirs (The True Memoirs).

If not for his Mémoirs, it is likely we would be a noted, but obscure figure today. Though he made contributions to policing, his fame is the result of his bestselling book.

Early Life

His delinquency began early. He described himself as the “terror to all dogs, cats, and children of the neighborhood” at the age of eight. He repeatedly stole from his father’s business, going so far as to fashion a false key to the open the money box. Significant because part of being a career thief, was being a master key-maker. After stealing a significant amount from his father, he ran away and, after being robbed himself, joined troupe of actors which is where he learned his talent for disguise; a vital aspect of his success as an agent of the police, and facilitated his numerous escapes. Upon returning home, Vidocq was arrested (during France’s Reign of Terror) and was sentenced to die by the guillotine. If not for his mother’s intervention, that would have been his end.

Vidcoq pursued by the gendarme. (Memoirs of Vidocq, Philadelphia, 1859)

Eventually, Vidocq had to leave Arras. He joined the military, deserted numerous times, and served on both sides of the war. He was a womanizer, dueler, and brawler, often finding himself on the wrong side of the law. He incarcerated more than once for assault, desertion, smuggling, or disturbing the peace, often escaping; sometimes for a few days, sometimes for years.

As for his conversion from criminal to police agent, Vidocq explained that he “began to grow weary of escapes and the sort of liberty they procured for” him and that “cruel experience and a riper age had convinced [him] of the necessity of withdrawing [him]self from these brigands.” (Philadelphia, 1859) That he was facing an extended sentence as a galley-slave cannot be seen as coincidental. He contacted M. Jean Henry, chief of the division of security in the prefecture of police, and struck a bargain.

Vidocq arresting Pons. (Memoirs of Vidocq, Philadelphia, 1859)

Police Career

Vidocq began his career as an informant on July 20, 1809 while still in prison, first in Bicêtre, and then in La Force Prison, where he was moved to in October. He collected information from his co-inmates and sent it along to Jean Henry through Annette (Vidocq’s then-wife). According to his Mémoirs, spying was a task he was well suited to, and he performed it so well that not even the prison’s staff suspected he was an agent of the police.

In 1811 (March 25 to be precise) Vidocq left prison in yet, another, escape. Or so it was made to look. In this instance, Vidcoq’s breakout happened with the assistance of the police. Success depended upon the criminal community of Paris accepting him as one of their own and trusting him. Something they were more likely to do if he were an escaped convict rather than an ex-convict released after serving his time.

This is significant, and necessary, for two reasons. First, many of the individuals Vidocq encountered fell into one of two categories: escaped or released convicts he had served time with; or, relatives/associates of convicts currently serving time. Second, the French system of law enforcement was dependent upon informers and spies and converting convicts in prison was an old practice. Reading his Mémoirs, it becomes apparent their reliance upon subterfuge, false identities, and alcohol to apprehend criminals.

Vidocq moved in and out of the criminal community, using his photographic memory, familiarity with the lifestyle, ability to mimic dialects, skill at disguise, and association with many of the members of the community to gain their trust. After all, Vidocq was one of them. He even bore the brands of a galley-slave to prove it.

He was as successful a spy outside of prison as he had been inside, and that success was recognized.

By the close of 1811, Vidocq had organized a number of other agents into an unofficial unit known as the Bridage de la Sûreté (Security Brigade). He oversaw them, trained them, and included them in a number of his jobs. Their success led the Paris police to make them an official division under the Prefecture of Police, with Vidocq as their leader. The decree was signed by Emperor Napoleon I on 17 December, 1813. This is considered to be the first detective division in the world.

There were eight of them at the start, and by 1824 they numbered twenty-eight. Most were former criminals, including his eventual successor Coco Lacour. They assisted the commissaries with search warrants, and carrying out the searches, they monitored the activities of known thieves, and oversaw the multitude of convicts (and ex-convicts) who operated as spies for the police.

Vidocq with the Old Galley Guard. (Memoirs of Vidocq, Philadelphia, 1859)

Methods of Policing

Policing in France at the start of the nineteenth-century, is unrecognizable to that at the end. Their “detective methods are limited to various acts of provocation, disguise, and incitement to betrayal” (Schutt, p. 61).

The arrests spoken of in his Mémoirs, (Philadelphia, 1859), were not the result of criminal investigations as we would recognize them, or physical evidence; they are more akin to undercover operations where the criminals are caught either with good that can be proven as stolen, or in the process of committing a crime. Vidocq does not go to the scene, gather evidence, and pursue suspects. Instead, he infiltrates groups of thieves, gains their trust, and gathers intelligence. Often, he does this through morally questionable methods including getting them drunk (illegal in today’s policing).

Once Vidocq had acquired information about future robberies—date, location, number of individuals—he delivered the information to the gendarmes, or to M. Henry, who arranged for police to be present to arrest the thieves mid-crime. In one instance, through deception and a borrowed handkerchief, Vidocq convinced the wife of a fence that her husband had been arrested and that she should remove all stolen property from their home. He went so far as to hire her the three hackney-cabs in which to transport the goods. Once she had the cabs loaded and they were on their way (Vidcoq accompanying her), the police surrounded them and she, and her husband, were arrested. (Philadelphia, 1859, pp 369-371)

Impact on Policing

Perhaps his greatest impact on policing is on the administrative side. As well as centralizing the detective department, Vidocq introduced a system of index cards for recordkeeping. They included detailed reports on the criminals, their physical appearances (including identifying characteristics), known associates, and methods of operation.

He understood the importance of physical evidence. He used a fragment of paper (found by the attorney-general of Corbeil) to identify and arrest highwaymen Raoul and Court for their assault on the butcher Fontaine. He used a nosebag, left behind at the scene of a violent burglary, to lead him to the coachmen Hussar who, when interrogated, led him to the gang of Savoy thieves who had committed the crime. Vidocq arrested an individual named Hotot for robbery based on an “imprint of two nailed shoes” found at the scene. Vidocq later matched the casts to shoes owned by the self-acclaimed thief. The shoes were obtained after Vidocq had plied him with liquor.

Title page of Memoirs of Vidocq, London, 1829.

End of his Career with the Police

Suspicions around his continued association with criminals followed him throughout his career. In 1827, whispers and accusations of impropriety could not be ignored, and he was forced to resign. (A change of leadership in the police also played a contributing role.) Vidocq made a brief return as head of the Sûreté in 1830, but under political pressure and rising opposition from rivals, he resigned again in 1832.

In 1833, he founded Le Bureau des Renseignments, (Office of Information) the world’s first private detective agency.

It began with eleven detectives, a secretary, and two clerks. Most of the people working for Vidocq (both men and women) were former convicts. He described the agency as defending citizens against fraudsters, imposters, and other criminals (faiseurs). As his opponents argued later, some of the bureau’s “cases” were morally questionable. In 1843, his agency was accused of forcibly transporting women to nunneries at the paid request of their families.

Their methods were not always legal and they often came into conflict with Paris’ police who were suspicion of Vidocq’s association with government agencies. This resulted in numerous raids of the agency’s offices and numerous arrests, even an attempt to exile Vidocq from the city for being an ex-convict.

After a final, brief trip to prison for fraud in 1849 (the case was dropped), Vidocq settled into a private life. He took on a few cases until frailty and illness prevented it. On May 11, 1857, Vidocq died at his Paris home in the presence of his doctor, lawyer, and a priest.

Entry in the Registry of Deaths at St. Denis, 1857.

“Je l'aimais, je l'estimais ... Je ne l'oublierai jamais, et je dirai hautement que c'était un honnête homme!”

'I liked him, I appreciated him I will never forget him, and I can just say he was an honest man!” — Alphonse de Lamartine

Bibliography

Gillingham, Lauren. “The Newgate Novel and the Police Casebook.” in Charles J. Rzepka and Lee Horsley (eds.) A Companion to Crime Fiction. (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), pp. 93-104.

Messent, Peter. The Crime Fiction Handbook. (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Schütt, Sita A. “French crime fiction.” in Priestman, Martin (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction. (New York, NY: Cambridge UP, 2003) pp. 59-76.

Vidocq, Eugene François. Memoirs of Vidocq: The Principal Agent of the French Police. Philadelphia, PA: George G. Evans, 1859).

Wagner, E. J. The Science of Sherlock Holmes. (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2006).

Worthington, Heather. “From The Newgate Calendar to Sherlock Holmes.” in Charles J. Rzepka and Lee Horsley (eds.) A Companion to Crime Fiction. (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010) pp. 13-27.